It was a rather quiet afternoon, an unexpected lull in the day. Dad got called into a meeting in Seoul and my brother, his wife, and the twins decided to go shopping. The gentle October sunlight flashed in and out through the balcony sheer curtains. Sitting on the floor with my back against the uncomfortably large leather sectional and my bare feet stretched in front of me, I finally felt like I was taking a break. Even the staticky Christian music from the radio seemed appropriate for the mood of the day.

Mom was in the kitchen area, humming to the radio. Now in her seventies, sporting a frizzy brown perm and a back brace, her movements were not as quick as they used to be. She complained that she has shrunk and was no longer 150cm, the cutoff height for not being under-tall. While achy bones and exhaustion was constantly on her lips, she never once looked frail or fragile. I guess that is what happens when you were a spitfire in your youth—you just mellow out.

After two years of forced separation due to the pandemic, I booked the first ticket to Korea the moment the quarantine requirements were dropped for immediate family visitation. As my parents grow older, a year seems to me about the longest I can justify separation. Back when they were in their fifties, there was a good six year stretch that we didn’t see each other or even talk over the phone. But somehow, that seemed fine, even preferred. We had lives to live and it wasn’t like I missed my parents. My childhood was fraught with hurt and misunderstandings. Even after I told Mom that I forgave her, the pain still persists. I have just become more at ease with my deviance from the norm and, now in my forties, absolutely unapologetic about it. Even comfortable.

I stretch my arms over my head and tilt my head back for a stretch and yawn. Looking around the living area, every nook and cranny is filled with tchotchkes and photos from when my parents used to travel. The low cabinet under the large TV was a shrine for her three granddaughters. A family photo with my husband when we came to Korea for a wedding reception two years after getting married was also there. That was ten years ago but since we don’t take photos, there wasn’t a good one for my parents to use to update their collection. The twins, pandemic babies, are now active and chattery toddlers and you could see the stages of their evolution from blob to human just by looking left to right. In between the artwork collected from the places they lived are planters big and small, mostly of orchids and succulents. My mom is from a farming family and she has always loved gardening. I saw that many of the containers had been moved out to the verandah to make space three adults and three children descending on the 1000 square foot apartment. Without any of her children and grandchildren close by, Mom cared for her plant babies.

There is a scent I call “my parent’s house”. I imagine that is different for everyone. It carries on even if they move houses. Mine is combination of flowers, earth, fresh laundry, wood, aged paper, and a hint of dwenjang and braised fish stew. None of the individual smells overpower each other and they combine to mean home. Even after mealtimes where we have to clean up half of the toddlers’ food from the floor, or ordering in food heavily spiced food because the adults are just too exhausted to fix a meal, or grilling mackerel on the stovetop, the apartment always reverts back to this familiar aroma. I had forgotten how much I missed it.

Now, I see two large pots and a skillet going on the gas stove in the kitchen. Without stopping, my mom says to me, “Can you come over here?” I respond, “Anything I can do to help?” and walk over to the counter next to the sink. She motions at the large bunch of scallions in the sink. “I ran out of chopped scallions. Cut them for me? Half straight, half at an angle. Put them in that plastic container when you are done. It goes in the freezer.”

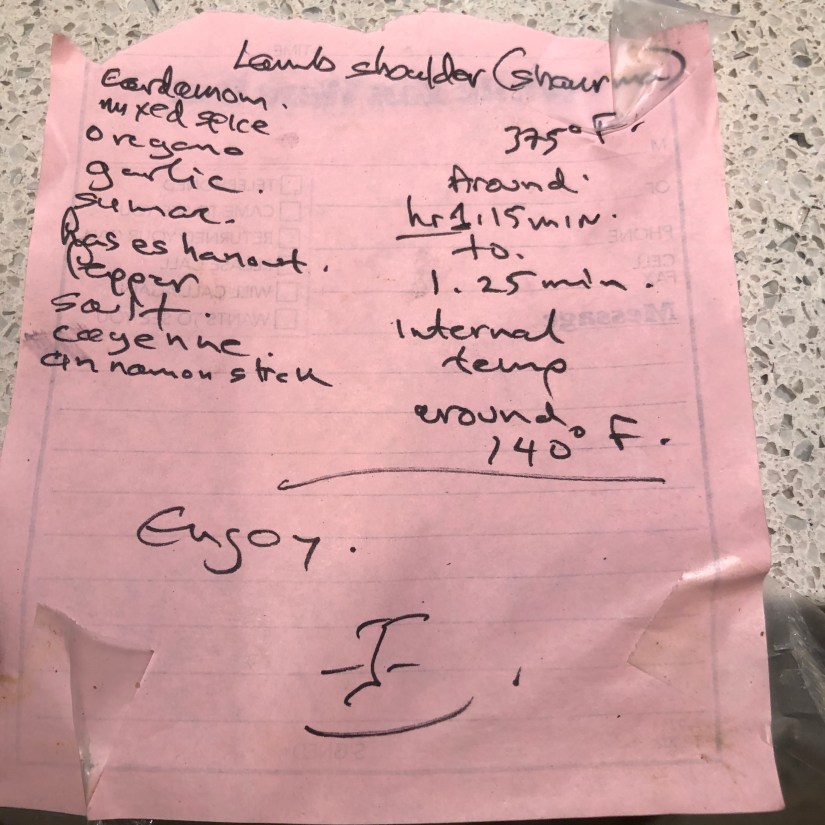

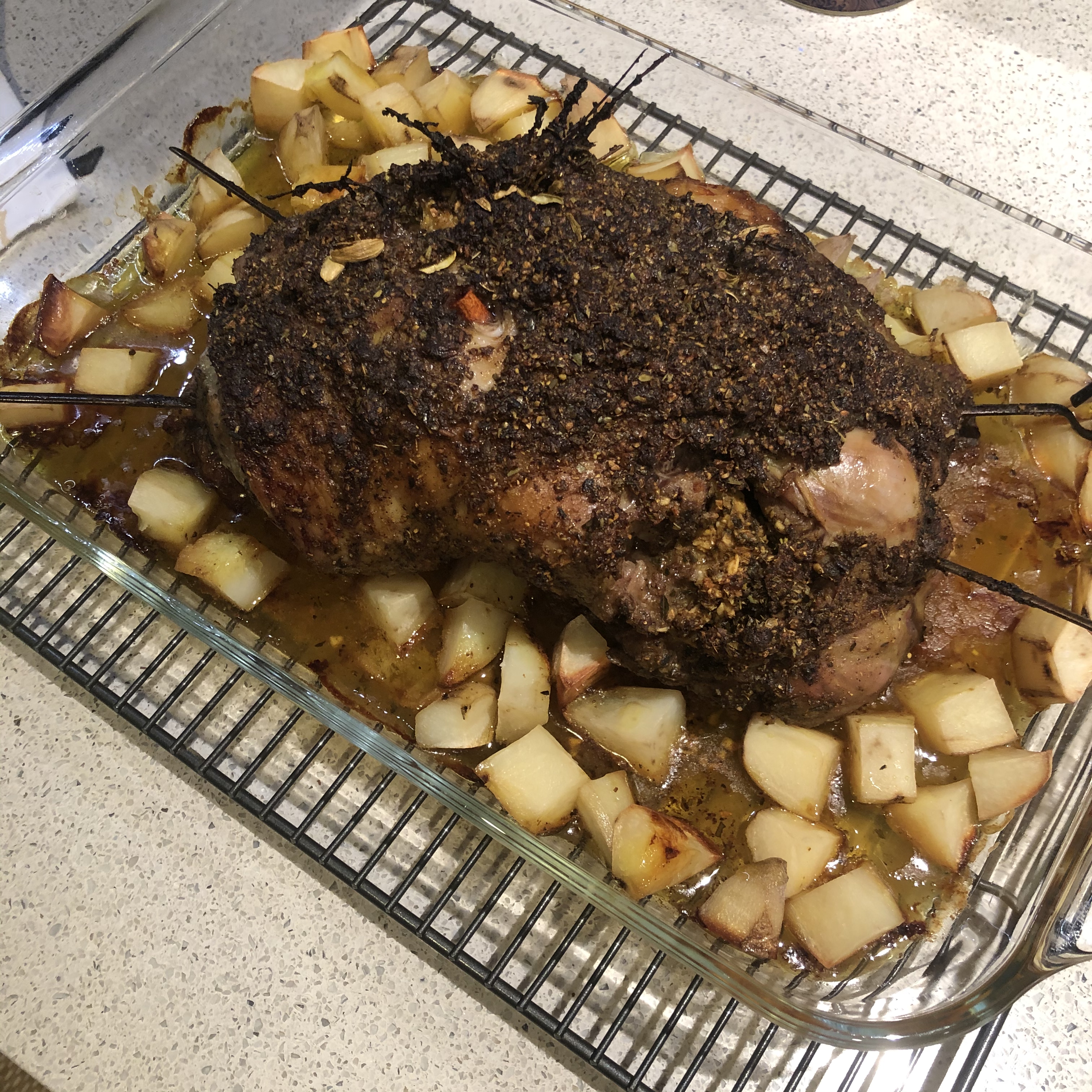

It dawned on me, right at that moment, that while this seemed so mundane, it was a very new exchange between Mom and me. When I left home at just as I turned eighteen to go to college in the United States, I never went back. The longest I spent with my parents after that was three weeks and it was always about ten days too long. When I started going to Korea for work, I would book myself a hotel room in Seoul and take the hour-and-half train commute to see my parents for dinner and never stayed over. Two years ago, we went on a road trip so barely ate at home. Until eighteen, I avoided the kitchen and anything that signified “girl”, at least outwardly. It was much later in life that I took interest in cooking and discovered my own aptitude. During the pandemic, I texted and called Mom for Korean recipes and cooking methods and she started following me on facebook and liked all my food posts. It connected us on a neutral territory as adults, without baggage. She admired my excellent knife skills and broad range of cuisines.

Before I could ask for the sharpest knife she had, she said, “Open the sink cabinet. You should see a knife with a wooden handle. Use that one.” The knife holder screwed onto the door had an eclectic collection of cheap looking knives. The one with the wooden handle poked out about two inches longer than the rest. I pulled it out and could immediately sense that it was very well balanced and fit into my grasp naturally. It was well honed and cared for.

“It cuts really well,” I remarked, swiftly slicing through the scallions.

‘”It was your grandmother’s,” she said. “It’s the knife she used all her life and I took it after the funeral.”

I imagine my grandmother bought the knife when they were still well off because the weight and balance of it was superior to my expensive German steel knives even if it was sixty or seventy years old on a conservative estimate. There was no sign of rust or wear, even for a blade that would have been sharpened and honed a few hundred times. The handle was still the original one, worn a bit and softened over time but still solid and firm in my grip. If there were any inscriptions about its origin, it had long disappeared.

My grandmother passed away after almost two years of suffering dementia and later leukemia. Dad’s younger sister was the main caretaker while she was in hospice care. There wasn’t much of an estate to speak of—an old, unrenovated duplex that was sold to make way for a highway, some photos and clothes, and basic kitchen goods. Like many Koreans, my grandparents lost everything during the Korean War. After the war, my grandfather, an engineer and entrepreneur built one of the first soju distilleries in Korea and Dad remembers living pretty well when he was a kid. However, for some reason, the business failed, his father died, and the family became bankrupt overnight. Since my dad was fourteen at the time, I am sure he knew why but, even to this day, he refuses to share the details. My grandmother had few possessions and I am certain my uncles and aunt took most things of value. I can kinda see Mom sneaking the knife into her purse when no one was looking while cleaning the house.

For both my mom and me, halmoni was a pivotal character in how we created our narratives. For me, she was the woman who raised me from birth. I was her first grandchild and much loved. My parents, newlywed at the time, both worked in a different city while living with mom’s brother’s family. My grandmother took me in so that both my parents could pursue their careers. For my mom, her mother-in-law was a modern woman, the first adult she knew who did not discriminate against her for being a woman. When she was pregnant with me, my grandmother ordered Dad to do the laundry, house cleaning, dishes, and obviously anything that required heavy lifting (he still does those chores). She was also supportive of my mom’s career as an elementary school teacher and volunteered to take me in so that she could work. This all happened in the 1970s in Korea. I recall that my grandmother was not a warm and fuzzy kind of woman and didn’t speak much. I also recall that she had a fiery temper and, being rather tall for a woman of her generation at almost five foot five, she could be intimidating.

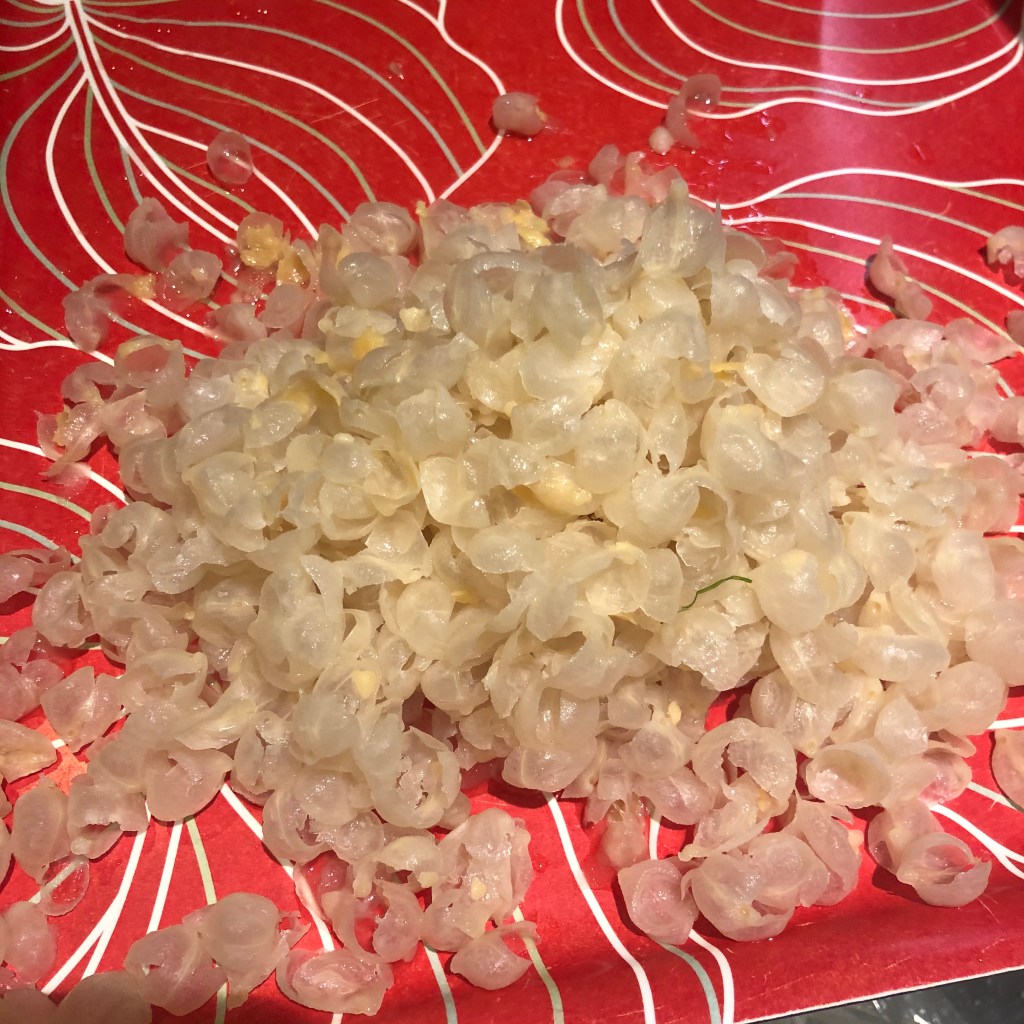

Kongnamul-gook, mung bean sprout soup, is the food I associate with my grandmother. It’s some of the cheapest soups you can make and it was always accompanied by a bowl of white rice and kimchi, not much else. My grandmother was not much of a cook and she always felt guilty for having Dad support her financially even while we lived abroad. For that reason, she was very frugal which meant a lot of mung bean sprouts in meals. Pieces of thinly sliced scallions floated on the surface of the kongamul-guk.

I choked back a tear and announced, “I am done. Anything else?”

I could hear a slight tightness in Mom’s voice as well. “Can you mince some garlic?”

“Sure,” I say. “How many?”

“Let’s start with five.”