When I was sixteen, I swore never to go back to Korea. Until then, Korea was where my brother and I spent most of our summer holidays, sometimes with both our parents, sometimes with just one parent, sometimes by ourselves. It was expected that we took the almost three day trek across the globe to see extended family. Back in the 80’s, in the height of the Cold War, the multileg journey went something like this: Accra-Lagos-Amsterdam-Anchorage-Tokyo-Seoul and then the reverse on the way back. As an angry and sensitive teenager, I hated my cousins who made me speak English even when I spoke Korean perfectly well, like I was a circus monkey. I hated that their friends would treat me like any other Korean kid until they found out I lived in Ghana and then spent the rest of the time making racist and ignorant jokes about Africans. I hated the rules and expectations that I had to follow as a girl that my younger brother could ignore. So at sixteen, I stopped spending my summers in Korea and stayed home in Ghana, mostly reading.

For this reason, I never truly learned to eat and drink in Korea. One thing I knew was that drinking with food was socializing and drinking without food was just one step away from alcoholism. As an adult, I learned a little from my brother who went to university in Seoul and then stayed to work. He knew where all the 맛집 (matjib: literally translates as “tasty house” or places known to have the best food, usually in one category) was and with him as a guide, I ate and drank well.

Many years later, I started traveling to Seoul for work about once a year and began to explore places on my own. One stop in the summer of 2018 was Gwangjang Sijang.

On our first trip to Korea, the Dude and I stayed in a place close to Gwangjang Sijang but we were too overwhelmed and full from a recent meal to enjoy the abundant street food. I could not forget the aromas literally steaming up from the hot griddles and cauldrons so the first chance I got, I sought out a 빈대떡 (bindaedduk: mung bean pancakes) stand. Bindaedduk is one of my favorite foods, only made occasionally due to the lack of ingredients in Ghana but a common street food in Korea.

Located in A-60, it is an outpost of 순희네 (Soonhee-nae: Soonhee’s House), the most well known bindaedduk eatery in the Market. There was a bench that seated about three people next to a griddle and a mechanized 맷돌 (metdol: millstone) grinding soaked mung beans into a large vat. It was lunchtime but I lucked out and snagged a seat next to a young woman who was eating by herself. I asked for bindaedduk and said how excited I was to have it since I have been dreaming about it for years (the truth!). I started chatting with the lady in front of the sizzling griddle with the pancakes spitting and crisping up to a golden brown. As she put a styrofoam plate covered in foil in front of me with the bindaedduk cut into small pieces and a side of sauce, she said “빈대떡엔 막걸리가 딱인데 (For eating bindaedduk, makgeolli is the best accompaniment).” So I ordered a bottle. Mass market makgeolli does not come in bottles smaller than 750ml and even if it’s about 6% ABV or less, it’s a lot of day drinking, but what the hell!

She also gave me some 완자전 (wanjajeon: meat pancakes) to try. A perfect bindaedduk is crispy on the outside and creamy on the inside, salty, savory, and filled with stuff. I turned to the young woman and asked in Korean if she would like some makgeolli. She replied in English that she was Japanese, and upon a repeat offer in English, she accepted. After she was done, she smiled and thanked me and left. My next neighbor was a pilot who was trying to purchase a bag of batter to take with him back home to Canada. I translated his request to the 이모 (eemo: auntie, strictly speaking, mother’s sister) and translated her instructions on how to fry it up to him. It was a glorious lunch, chattering with strangers and filling my belly. The bindaedduk-makgeolli combo, while classic, was one that I had never had before and I had a strange coming-of-age feeling. I promised to return. At the time, I didn’t realize how soon that would be.

About fifteen minutes later, as I neared Kyungbokgoong, it suddenly dawned on me that I had not paid for my meal! I hurried back, red from walking fast in the heat, completely embarrassed. I sheepishly apologized and asked how much I owed her. She looked at me with a wry smile and said, “그냥 가지 (you should have just gone).” Her assistant chuckled and said she was trying to treat me to lunch. She accepted the money but then gave me a large bag filled with bindaedduk and wanjajeon. I teared up a little.

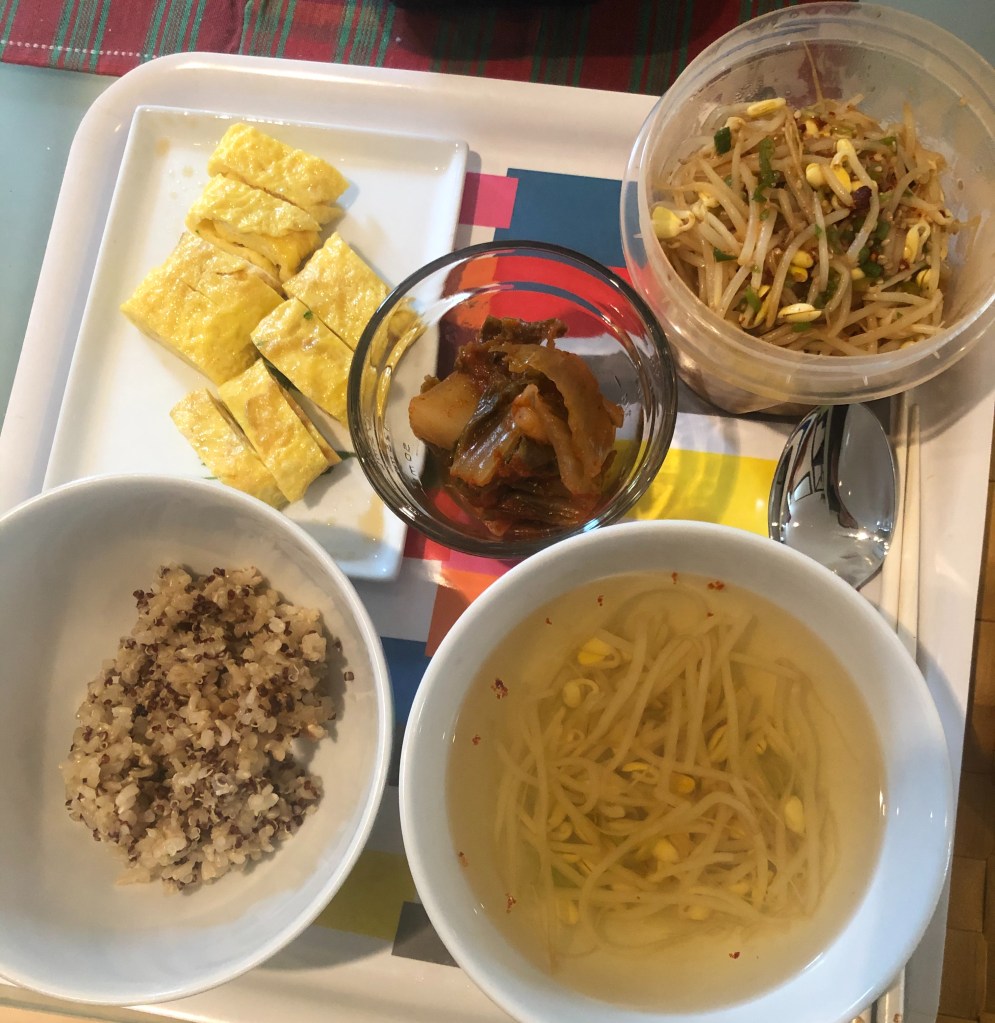

During the pandemic, I made bindaedduk a few times but it was never like the one in Gwangjang Sijang. For one thing, it takes griddle mastery to get the oil temperature correct. Plus, Soonhee-nae probably has a secret recipe to have just the right consistency. Nevertheless, here is my recipe.

빈대떡 (Bindaedduk)

- 1 cups split mung beans (The yellow beans look like tiny yellow split peas. You can also use whole mung beans and gently rub of the skin after soaking.)

- 1 cup water

- 4 Tbsp glutinous rice flour (Alternatively, you can soak 1/4 cup glutinous rice with the mung beans.)

- 1/2 cup napa kimchi, chopped

- 1 scallion, chopped

- 1/2-1 cup various other stuff like bean sprouts, ground meat, leftover banchan, etc.

- 1 Tbsp sesame oil

- Salt, pepper, sesame seeds to taste

- Soak the mung beans for about 6 hours and drain well.

- In a food processor, grind the soaked mung beans and water but not too finely.

- Add glutinous rice flour and mix.

- Add the rest of the ingredients and mix into a thick batter.

- Let it rest for about 20 minutes.

- Heat oil gently in low heat in the griddle or cast iron pan or frying pan.

- Add the batter in small scoops, about 1/3-1/2 cup (do not crowd the pan).

- Flip over when golden brown and fry until cooked through and golden brown on both sides.

You can keep the batter in the fridge for a day or two.

I have not been able to replicate this experience for years because finding makgeolli in Philadelphia is almost impossible unless you go to an HMart with a liquor license (too far for me without a car) or special order it through the PLCB. Recently, I discovered Hana Makgeolli, an artisanal makgeolli brewery in Brooklyn that would ship!

I burnt this batch a bit, and it is tasty but not even close to stand A-60 in Gwangjang Sijang. As I wait for the day I can travel back to Korea for the full experience, this will have to do.